Susana Guerrero, SFGATE | on February 6, 2018

By the time Donaldina Cameron arrived to the Chinatown building, tucked away in an unassuming alley, the girl was already taken.

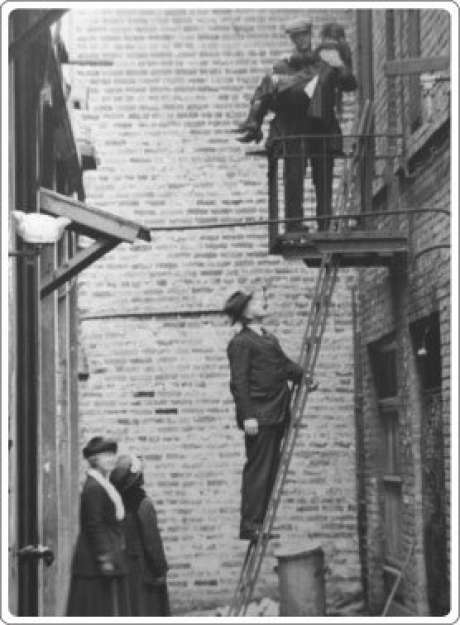

At 5 a.m. the building on St. Louis Alley was surrounded by three officers of the Juvenile Court, several mission workers and federal agents that accompanied Cameron as they prepared for the ambush. Their purpose was to rescue 13-year-old So Jy, a Chinese immigrant girl who was being exploited as a slave.

“[Cameron] placed men on guard at the two entrances to this alley as well as on surrounding roofs and then began chopping away at the heavy, double-boarded door which barred the stairway leading to slave quarters above,” the Chronicle reported in 1914 in a recount of this undated incident.

The building was the supposed residence of a well-known liquor merchant, but it was just a front for a slave house that harbored Chinese immigrant girls and young women.

Cameron, the superintendent of the Occidental Mission Home for Girls, wasn’t new to raids.

She had a knack for tracking down buildings that trafficked Asian immigrant girls who were forced into the sex trade or indentured servitude. On this day, Cameron and her group managed to break into the home, thanks in part to a child operating from within, but failed in the rescue attempt. Inside, they only found signs of a hasty departure.

With some luck, they discovered a hidden door behind some paneling. The door led to a passage that connected to an adjacent apartment, which then led to the discovery of another concealed door. That door finally revealed a staircase with an exit onto Grant Ave.

The only logical escape route, they decided, was through the residence of a Chinese merchant on the floor above the original house under siege.

“Here the raiders, admitted after tumultuous protest and every show of righteous indignation, found five slave girls, fully dressed, hidden between the covers of several beds,” the Chronicle reported.

Unfortunately, Jy wasn’t among them.

Cameron later learned that Jy had been moved the day before because “her owner” anticipated a raid. She made two more attempts to rescue the girl after receiving tips about her whereabouts, but Jy was never found.

*****

Such were the days in San Francisco during the 1870s to the early 1900s when prostitution and slavery, particularly among Asian women, was rampant.

In 1876, a man named Dr. O. Gibson, waged the first campaign against the smuggling of Chinese immigrants into the U.S., estimated that there were 2,600 Chinese sex slaves in San Francisco. Gibson added that there were “only 120 Chinese women ‘of respectable character'” in the entire city, the Chronicle wrote in 1914.

Two years earlier, the Occidental Mission Home was founded by the Presbyterian church to help save young Asian immigrants escape slavery and the sex trade by means of faith.

Donaldina Cameron arrived to the house at age 25 in 1895, originally to teach the girls how to sew, but quickly became the superintendent after the death of her predecessor.

To the girls she rescued, Cameron was known as “Lo Mo,” Cantonese for “mother” but to the tongs, an organization known for running brothels and for threatening Cameron, she was best known as “Fahn Quai,” or “white devil.”

“Even when they planted dynamite on her doorstep or hung an effigy of Cameron with a knife in its heart, they never broke her resolve to end the prostitution racket,” Laurene Wu McClain wrote in her essay, “Donaldina Cameron: Woman who Helped Free and Take Care of Slave Girls from China who Were Brought to San Francisco in the 1890s.”

Despite the threats, Cameron went on to rescue a total of 3,000 girls before she retired in 1934. By 1942, the home changed its name to the Cameron House, their website notes.

Today, the Cameron House has shifted their initial mission, but continue to serve the Asian community by helping low-income immigrant families and individuals in San Francisco.

Follow Susana Guerrero on Twitter and email her at sguerrero@sfchronicle.com